Experienced African American genealogists will all tell you the same thing. To trace your family history beyond the 1870 brick wall, you will have to spend some time tracing that elusive slaveholder; commonly referred to as enslaver, for the sensitive. Sorry, but there is no way around it. I was able to trace them, and this is part of their story and ours, and I’m sharing it with you. My goal is to provide the historical context of our family and make this common knowledge. Mi Casa is tu casa, and my research is your research. So, grab some coffee, sit back, and relax. This is going to be quite the post.

But first, a word of warning. Some will find it challenging to review the subject of those previously enslaved without experiencing intense emotions. Rest assured that it’s ok. Society has always seemed to sweep slavery’s history under the rug. Even African Americans in the early years were embarrassed by it; “Hush child, we don’t talk about that.”

This mentality has changed in today’s day and age, and now we all want to know our history. Again, this can still be painful. Even the word slave is controversial, and the politically correct term today is enslaved. But a rose by any other name is still a rose, and the same can be said for slavery.

In this blog series, I have zero intentions to make slavery appear anything other than it was. You might even see the names of our ancestors with dollar values assigned to them. However, I urge you to use this blog to reflect on what our ancestors went through. Not just their pain, but their post-emancipation triumphs. Because of them, we can not only survive but can thrive. I’m using this blog to tell their stories as best as I can. The ultimate goal is to discover where we came from in Africa.

To start off, let me just say I get it. Some people don’t want to tie “the white man” enslaver into their research or even spend time thinking of them. As our Italian mafia friends will tell you, “Fuggedaboutit!”. (Forget about it, Insert Italian mafia accent and voice here). However, if you really want to move forward in your research, this is not an option. Especially when you consider that your ancestor could be a descendant of “the white man.” Check your DNA results if you don’t believe me. You might find that you are not entirely descended 100% from Africans. You are what you are.

Getting Started

So, you want to start tracing that elusive slaveholder as soon as you have exhausted your Census research, beginning with the 1870 census. Don’t forget to employ the community clustering method, and while you are at it, get a DNA test. You might get lucky and either connect directly with descendants or find a relative like Alex Haley that has already completed the research. Slaveholders are not elusive because they tried to stay hidden. It’s just that the records from so long ago can be challenging to uncover. Being thorough is a must. Check every clue and every lead. Look under every rock and leave no stone unturned. Sometimes you might miss something that has been staring you in the face.

Remember that 1870 census? Everyone probably knows by now that you look for the closest white resident, check to see the Census listed “Value of Real Estate” and “Value of Personal Estate,” and maybe check the surname while you are at it. Some blacks took the name of their slave owners at emancipation, but careful, as this is not always the case. Professional genealogists suggest that researchers look several pages back and several pages forward to look for communities. Again, this is the community clustering method.

The Winters and Scales Slaveholders

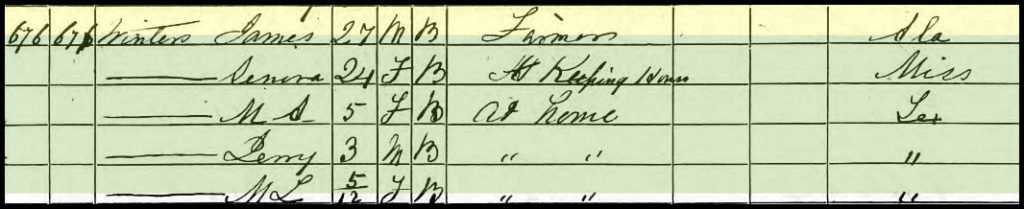

I must admit that when I first started researching, I had no idea about using community clustering. I looked at the census records, and all I could see was a bunch of names that looked like ants. Those names still look like ants today, primarily because they were written in cursive. I had overlooked a key fact in my early days of research. My great-great-grandparents James Winters and Senora Scales were on page 57 of the 1870 Census for Washington, Texas, Subdivision Beat 1. The white descendants of the slaveholder, Sarah Ann Hogan-Winter, was on page 52. You can read her story in part 2 of this blog.

Honestly, my discovery was entirely by accident. Correction, I believe it was divine intervention as I wasn’t even looking for it. While in Texas for the 2019 Winters Family reunion, I visited the Washington County, Brenham, Texas courthouse. I was looking for land owned by James and Senora in the later 1800s and was taking pictures of the documents that I found. Then, unknown to me at the time, I inadvertently took a few pictures of deeds for Sarah Winter.

Those accidental pictures were the key to unlocking that 1870 brick wall. They didn’t completely shatter the wall, but they provided me with valuable insight. Genealogists consider finds like these as pure gold. However, every story will be different because you never know what you are going to find. Discipline, consistency, and diligence are traits that will be required if you are to be successful. The most important thing is never to give up. You might not find them in a day, or a week, or maybe even months. The thing to remember is that it is not impossible. Just keep searching!

The Power of Technology

As most know, I don’t live in Texas. I live in Washington State, 2200 miles away. This prevents me from visiting the Brenham courthouse on an impulse. Fortunately for us, several of these historical documents have been digitized and are available online. However, this is not the case for all of them, and you will have to call the courthouse and inquire. You simply need to know which courthouse will have them and find their site online. Thank God for Google! For Brenham, their site is at http://www.edoctecinc.com/. You can find records such as land, marriage, births, deaths, and military.

Thanks to my initial courthouse visit, I had found a will that included Sarah Winter in it. But it wasn’t her will. It was for a person named Authur Smith Hogan. The will wasn’t even written in Texas. It was written in Alabama and was dated 1849. it was a copy. Remember, there were no copy machines back in the 1800s. Every copy of a document had to be handwritten. In cursive. So why was this Alabama document located in a Brenham County, Texas courthouse? As far as my previous family research was concerned, there were no Hogan surnames or much of anything in the state of Alabama. Again, this is the reason why diligence is so crucial. If you aren’t careful, you can miss the elephant in the room.

As it turns out, the short story is that Sarah Winters was the daughter of Arthur Smith Hogan, and she had migrated to Texas in 1862 along with several family members, friends, and slaves. But I’m getting way ahead of myself. Let me start from as far back as I can go.

So who was the Slaveholder? The Story of Arthur Smith Hogan

In the updated writing of The Winters Family book (unreleased to date), I go into details on the known slaveholders. But this is an online blog, so I’ll need to keep it brief. You’ll be able to read more details when the book is released. Let’s just call this a summary.

Arthur Smith Hogan was born in Halifax, North Carolina, in 1776. That’s important because we have DNA relatives and Census records of family from North Carolina. This is especially true of the Scales side. In fact, Julius Scales, the father of my great-great-grandmother Senora Scales, was born in 1814 in Alabama, but his siblings and family were all from North Carolina. I can explain why, as I have traced them, but that’s an entirely different topic that deserves a separate blog.

On a side note, multiple DNA matches also connect us to another man from North Carolina. A historically significant freed mulatto slave named Jesse Reuben Cotton (1785-1862), and his wife Jennie Griffin. Currently, I’m not sure which of them was our ancestors, but all of their children are our DNA matches. You can read about him here. Their late 1700’s/ early 1800 cabin is still standing today. I hope to write a short blog about them and our related white and black DNA matches. I do cover him in our book, though. For now, let’s continue with Arthur Hogan of North Carolina.

Roots In North Carolina

Thanks to the Race & Slavery Petitions Project, while researching Arthur Hogan, I stumbled across the 1833 Alabama Supreme court case of Arthur S Hogan vs. John Belle & Wife. You can read a brief synopsis of the case here.

The Project offers a searchable database of detailed personal information about slaves, slaveholders, and free people of color. Designed as a tool for scholars, historians, teachers, students, genealogists, and interested citizens, the site provides access to information gathered and analyzed from petitions to southern legislatures and country courts filed between 1775 and 1867 in the fifteen slaveholding states in the United States and the District of Columbia. It’s a very valuable resource, so check it out.

The case started in the Franklin County, Alabama lower court before it was elevated to the Alabama Supreme court. What makes this case valuable for me is that its related documentation does not only provide the names and ages of the slaves, but it also indicates how they were related to each other! It was quite the find.

According to the case, Thomas Blount Whitmill, also of Halifax, North Carolina, died on Sept 20, 1798. I’m not sure of his age. According to his last will and testament dated Sept 10, 1798, he passed his slaves to his children. These were Elizabeth West Whitmill, son Thomas Whitmill, son Drew Smith Whitmill, daughter Ann Smith Whitmill, and son Thomas West Whitmill. And yes, before you ask, he had two sons with the first name of Thomas. To keep this blog condensed, we will primarily focus on his daughter, Elizabeth West Whitmill, who would eventually marry the latter slaveholder, Arthur Smith Hogan. Arthur Hogan’s nickname was Art.

A court witness by the name of William Alsobrook testified that a short time after the death of Elizabeth, John Bell was at the house of his brother-in-law, Art. It was then that John made a demand of him for the negroes. Art’s reply was he was not willing that anyone should see or borrow his negroes, and that “Whatever you could do to compel me to do by law, you are at liberty to do so.” (petition page 15). Apparently, Arthur didn’t seem to care much for his brother-in-law. And with that, Arthur refuses and was unwilling to give up the slaves he acquired from his now-deceased wife, Elizabeth. And as they say, that’s when the fighting started. And I don’t mean that figuratively. John Bell and his brother-in-law, Arthur Hogan actually got into an all-out fight, detailed by witnesses in the court case, blow by blow. Arthur even walked with a limp for a while.

I imagine the giddiness of the slaves when they saw their master in a fight. What was going on in their minds? Maybe John Bell did to Hogan what they had wanted to do for decades. Or maybe, they thought that although in slavery, Hogan treated them right? Purely speculation. Tell me your thoughts in the comments!

Well, actually, the fighting started a little later, when John Bell and Arthur’s met for deposition of a witness. This would make a great scene in a movie.

Witness testimony of John Acre, at Stewart County, Tenessee, dated July 25, 1831. He was at the house of Mr. Jones to take a deposition of Silles, a testifying witness in the case.

“This occurred between the above parties (Hogan vs Bell) on the day I got to Mr. Jones’s place for the taking of said deposition. Shortly after I got there, several of the neighbors came in. While I was in the house, I heard Mr. Jones say that John Bell should not come in his house on that day. Myself and a Mr. Hicks immediately walked outdoors and set under a shade tree some distance from the house. Not long after which I saw John Bell riding up and, in a few minutes, I heard him (Bell) call out for me. I rose up and went and met him. He then told me that he could not be admitted into the house to take Silles’ deposition, and asked myself and esquire Polk the other Justice to give him a certificate to that effect. I spoke to both Mr. Bell and Mr. Hogan and told them that as the parties could not be admitted into the house, that we would take the deposition under the shade (of the tree) which I first thought they would consent to.”

“But finally, Mr. Hogan refused to do it and said that the intent was for taking the deposition in the house and it should be so and that John Bell could stand at the door and cross-examine if he thought proper which Mr. Bell refused to do. Hogan then stated that if he (Bell) had treated Mr. Jones as a gentleman, there would have been nothing of it. Bell then stated that he had treated Jones as he deserved. Then Hogan turned off and stated that the deposition should be taken in the house and Hogan further said that other men had had to stand at the door and cross-examine and that Bell might do it if he thought proper.”

“Immediately Bell struck Hogan with a stick and staggered him very much, and in the act of recovering, Hogan drew his knife and made at Bell. Bell then gave him the 2nd lick with the same stick and felled him to the ground and pitched on him. I saw Hogan cutting at him with the knife. I took hold of Bell and tried to pull him off, which brought Hogan uppermost, and instantly, several other persons rose up and we broke them up. As soon as this was done, Bell ran and got upon his horse and asked me if we might go to my house, which I of course granted, and he accordingly set out directly. While Bell and Hogan were engaged on the ground, John Jones and William Jones picked up a large rock apiece. But what they intended doing with it, I am not able to say. I ordered them to throw them away which they immediately did. We then took Hogan into the house, washed him, and after giving him time to cool, proceeded to take the deposition of the said Silles.” (Page 19)

The case took 6 years to resolve and includes a whopping 54 pages of PDF content. I break down those 54 pages and go into detail in the updated Winters Family book (again unreleased to date). Those pages provided me with a valuable glimpse into the lives of the slaves.

Thomas Blount Whitmill’s had 16 slaves and six of those were inherited by Hogan through his wife, Elizabeth. The slaves could have been related but were separated by Thomas’ will. One thing I have learned while researching is that the names of past relatives were given to their children. When we look at Arthur Hogan’s 1849 Last Will and Testament in part 2 of this blog, we will see new generations of slaves with some of those same names. Charity, Molly, Charlotte, Hannah, Phillis, and Wilson to name a few. However, some of those are names of slaves from Thomas that were not inherited by Arthur Hogan. While we can’t say for certain that those slaves were related, it certainly is a coincidence.

The names of Thomas Whitmill’s slaves at his death were Jerry, Charles, Hannah, Charlotte, Ben, Homer, Susan, Phillis, Wilson, and finally he “loaned to his daughter Elizabeth West Whitmill six negroes to wit: Sam, Eli, Charity, Tempey, Lewey and Molly and their increase during her natural life and if my daughter Elizabeth West Whitmill should have an heir or heirs lawfully begotten of her body, I then give the said heir or heirs begotten of the said six Negros above named and their increase to them and their heirs forever.” Those six slaves were the subject of the court case.

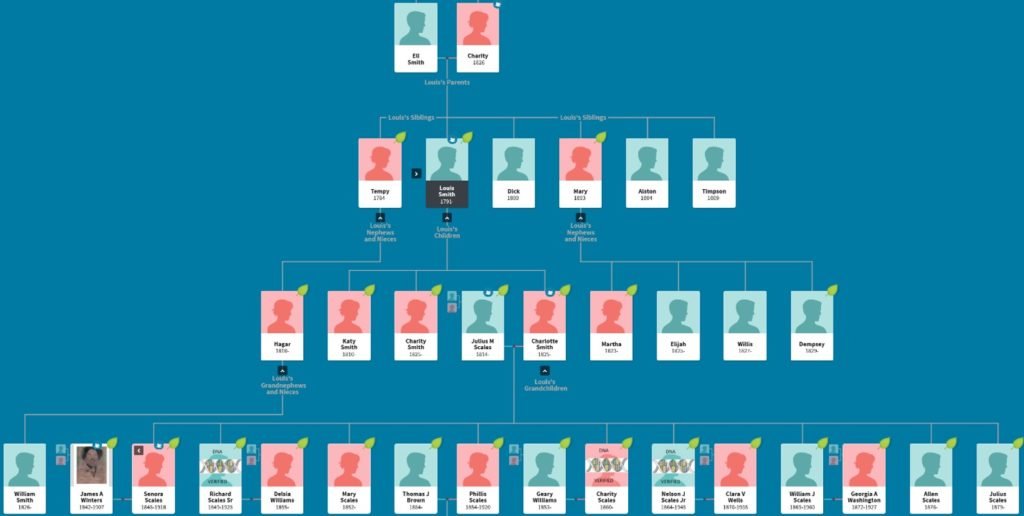

If you are a Scales descendant, then some of the names from that 1833 list should look and sound familiar. In the 1870 US Census for Washington County Texas, we see that Charlotte (born ~1825) was the wife of Julius Scales (born 1814). These are my 3x great grandparents! They had several children, including my great-great grandmother Senora Scales, and her siblings Richard Scales, Mary Scales, Phillis Scales, Charity Scales, Nelson Scales, William Scales, Allen Scales, and Julius Scales Jr. However, I want to particularly point out that Charlotte chose the names Mary, William, Phillis and Charity Scales for four of her children. All of these, names appearing on that 1833 Supreme court document. Keep in mind that the oldest of Charlotte’s children, Senora, wasn’t born until 1845, which is twelve years after that slavery list was written. So Charlotte’s children are not the same individuals from the Supreme Court list.

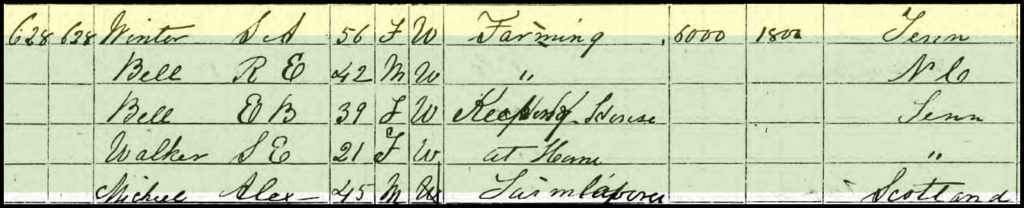

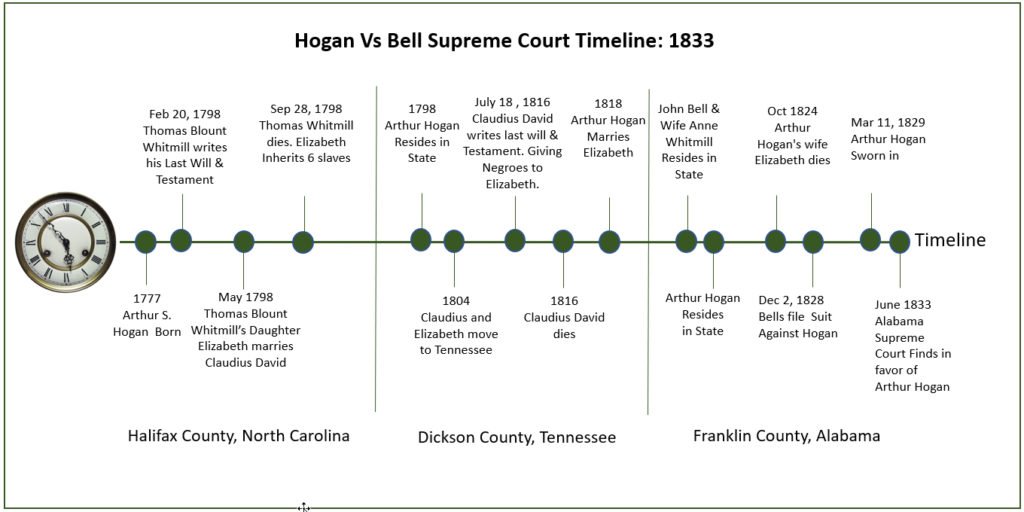

The 1870 Washington census shows that Louis Smith, (Lewey) was born in 1790 in North Carolina. He is living with two females, a Katy Smith, born in 1810 in Tennessee, and a Charity Smith born in 1825 in Alabama. Right below him on that census page we see Charlotte as the wife of Julius Scales. All of their birth locations and time frames with the Supreme Court timeline and Arthur Hogan’s geographical movements from North Carolina to Tennessee to Alabama (See timeline below).

The “Ah-Ha!” moment is when we look at the 1880 Washington, Texas census for Julius Scales, his wife Charlotte, and their children. We then see Lewis (Louis) Smith listed as Julius’ FATHER-IN-LAW!! We just learned that Charlotte is the daughter of Lewis! Identified as Lewey in the court case, he is part of the original 6 slaves in a legal battle. Also, as I read into the case, I discovered that Lewis was in fact, the child of Charity. Per the court case, she died in 1826. So picking up on the names of the slaves left at Thomas Whitmill’s, Lewis named his daughter Charlotte, and Charlotte named one of her daughters Phillis, and another after her grandmother, Charity. This leads me to believe they were all related. Coincidence? I think not.

Can you imagine the stories that Louis could have told of our family history? God blessed him to see his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. I lose track of him after the 1880 census and have no record of when he passed away.

By the way, James Winters and his brother Alex Winters were both born after the 1833 Supreme Court case. For them, we will need to peek at Hogan’s 1849 Last Will & Testament. See part 2 of this blog.

I am providing a timeline as it provides an excellent summary and makes things easier to follow. In North Carolina, Thomas Blount Whitmill’s daughter Elizabeth marries Claudius Bell. In his will, Thomas B. Whitmill states that he lends(not gives) six negroes to his daughter Elizabeth. Therefore, at her death, her sister Ann and husband sought to get them back.

It’s quite the story, as, by 1825, those six slaves had increased in number, totaled 15, and were valued at $5,550. However, I believe that the total number was higher, and deception played a part.

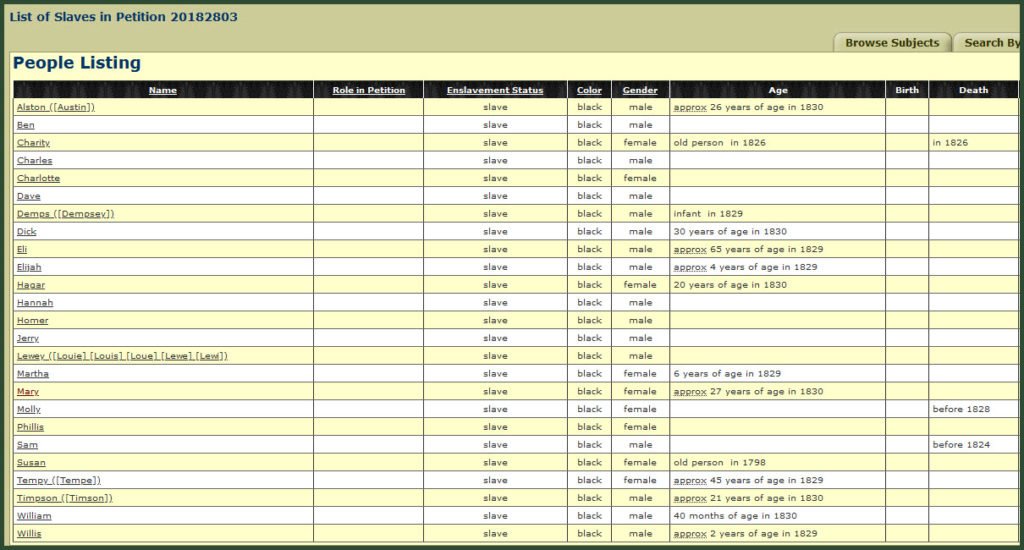

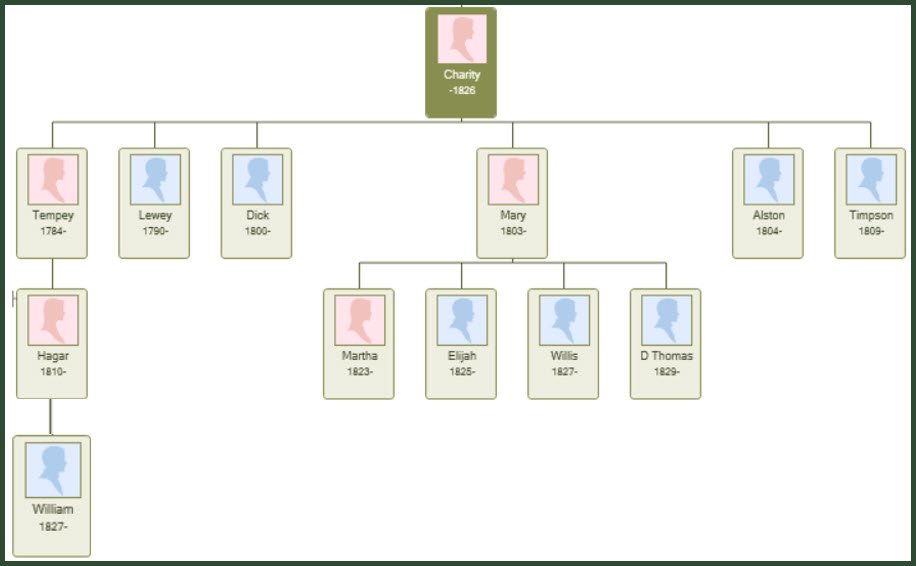

Genealogy of Charity

The original six slaves listed, Sam, Eli, Charity, Tempey, Lewey and Molly. One of the slaves on the plantation was killed, but I can’t remember the details, or who that was. One thing is for certain was that Arthur didn’t seem to be entirely honest about the slaves’ increases. I created a tree based on the court records. Charity passed in 1826. If you look at Charity’s tree that’s shown in the image, Arthur does not declare any children descending from Charity’s four sons. If he did, he would be ordered by the Supreme court to pay for every one of them, which is something he obviously didn’t want to do. For example, we know that Lewey (Louis) had at least three who are Charlotte, Charity and Katy.

Per the testimony of Drew Champion, Sam and Molly were married. However, by the time of the court battle, Molly had died before 1828, and Sam before 1824. I found the fact that they were married interesting as some slaveholders did not allow marriages. Did this mean that Hogan honored the slaves’ relationship with each other? If they did, it would help to determine relations when he divided the slaves up in his Last Will and Testament. I’m not sure about Eli.

Fortunately, the document further clarifies the children’s ages, but I can’t quite tell the year that this portion was written. Besides her children Tempey and Lewey who arrived with her, here are the children and grandchildren of Charity, one of the original 6 slaves (she died on March 1826); Dick 30 years of age, Mary 27 years old, Alston about 26 years old and Timson, about 21 years old. The grandchildren of Charity from her daughter Mary are as follows; Martha 7 years, Elijah 5 years, Willis, 3 years & Dempsey 1 year old. Tempey, also one of the original 6 slaves, had a daughter named Hagar who is 20 years of age and gave birth to a grandson, William who was 3 ½. The children constitute the “increase” from the slaves as mentioned in Thomas Blount Whitmill’s will.

Here is the testimony of Drew Champion, as recorded on July 29, 1831, in Franklin County, Alabama. Drew was born in 1769. The court had asked him if he heard Thomas Blount Whitmill say certain words regarding a gift that he had made of some negroes that he had given to his daughter Elizabeth. He inadvertently drops an important clue about Eli.

“….(Thomas loaned)his daughter Elizabeth; Charity, Eli, Sam and his wife Molly. Sam was sold by my father to Whitmill. I also recollect of seeing the negroes at Claudius David until he left the county which was several years after their marriage. What makes me recollect more particularly about Eli is that Whitmill & myself bought three negroes from a Virginian. Eli was one of the three”. – Drew Champion

To quote the witnesses of the Alabama Supreme court here is one of the many excerpts concerning the slaves. A quick warning is that it might draw emotion as it reduces the value of their lives to a dollar amount. However, that value is a clue to the slaves’ age and ability. For example, per the court records, Lewey was a shoemaker.

“…That Molly was old, since dead and of no value. That Eli is worth about $300 and is worth $80 annually. Charity is worth $250 and $60 annually. Tempy is worth about $400 and $70 annually, Lewey is worth about $700 and $125 annually. They further shew unto your honor that the woman Tempey since said devise has had one child, Hagar worth about $500 and $100 annually, Hagar has had one child named William worth $250. Charity since said devise has had four children, Dick worth $600 and $120 Annually, Mary worth $400 and $70 annually, Alston worth $600 and $120 annually, Timpson worth $600 and $120 annually. Mary had had four children, Martha worth $300 and 25 annually, Elijah worth $400 and $30 annually, Willis worth $200.”

I should note that Arthur Hogan came up with his own numbers, as indicated in his testimony below, dated March 11, 1829. Naturally, he wanted to show them at a reduced cost in case he lost. Notice the differences in their perceived worth.

“The Respondent further answering says that of the negroes mentioned in said bill, Eli is between sixty and seventy years old and is not worth more than $100 and is not worth more than $80 annually. Charity died in March 1826 although the complainants represent her as now alive, was an old negro and is not worth more than $100 nor more than $18 annually. Tempey is about forty-five years old and is not worth more than $300, nor more than $40 annually. Lewey is worth about $450 and $100 annually. He admits that Tempey since said devise has had one child, Hagar who is also not worth more than $375, nor more than $50 annually., and that Hagar has had one child William, not worth more than $100. He admits that since said devise, Charity has had four children. Dick who is worth no more that $400 nor more than $75 annually. Mary worth about $300 and $20 annually. Alston worth $450 and $100 annually, and Timson worth also $450 and $100 annually. He also admits that Mary has had four children of which Martha the oldest is six years and not worth more than $175 and not worth anything annually. Elijah, still younger than Martha is worth about $175 and not worth anything annually. Willis still younger is worth about $75 and Dempes a small infant not more than $50.

To skip all of the juicy details, in August 1831, the lower court of Franklin County, Alabama court found in favor of the John and Anne Bell, the complainants, and ordered Arthur Hogan to pay $4578 and deliver the living slaves to John and Ann Bell. However, in January 1832, Hogan appealed to the Alabama Supreme Court, which continued the case in January 1833 and reached its conclusion on Jun 29, 1833. The Alabama Supreme Court decreed that the lower court decision be reversed and annulled, and it allowed Arthur to recover against John Bell for any court costs.

Long story short, after a 6-year journey, Arthur ended up keeping the slaves and their children. Don’t forget to read part 2!

Pingback: Tracing That Elusive Slaveholder – Part 2 | Tracing Lineage

Thanks Leonard for all your work in helping to educate us. We owe so much honor and respect to those who came before us, who ensured the atrocities of the oppressors. I hope in this journey you are able to locate the living family members of those who stole our rightful inheritance our ancestors work so hard to obtain.

No where in your reporting did you write about our family members having strife against one another, but the hatred you write about came from the oppressors because of greed!! And this greed continues to be embedded mentally in all the evil enslaved ones today.

You have given me information about places I now feel I need to travel to, such as North Carolina, Alabama, Tennessee and Mississippi. I’ve traveled to all these states before, but not for the purpose of connecting to my roots.

Thank you so much and may God bless you.